Oppression, Privilege, and Allyship

In addition to more technical game development workshops, Rad Studio included a significant social justice curriculum. This blog post is transcribed from a workshop that was presented early in the summer to define terms like “oppression,” “privilege,” and “allyship” that would form the basis of many other workshops to follow.

The discussion centered on game development spaces specifically, but we spent some time defining universal terms and talking about privilege on a holistic level. Before diving in, we recognize that many people in the room (or those reading this blog post now) intimately understand the effects of oppression and privilege because we live those effects. Thanks for hanging out with us today and listening or reading along. We hope that this is helpful to you, too.

“We can’t work to fix something unless we first see and understand its effects.”

-Jonathan McIntosh

This workshop was created because, as noted above, we can’t make social progress against oppression until we understand its effects. The other reason why we're talking about this is because creating video games does not exist in a vacuum. There's a very powerful history and culture surrounding the video game industry that everyone entering the industry absolutely needs to know about. As we said, we know a heck of a lot of you already do, but some of you don't and it's critical that you understand what culture you're going into so that way you can make a conscious decision about how you want to contribute to that culture.

Content warning

We will be discussing some kind of difficult issues today. Specifically, issues surrounding inequality like racism, sexism, and ableism that might be triggering for some folks. We're going to be talking specifically about alcohol, abuse, and sexual & racial harassment in the workspace as well.

Disclaimer: Megan and Dana are both white, middle-class people.

This presentation was prepared by two white, middle-class people and we want to unpack our privilege in that way so that you all can understand that we lack a critical perspective here on some of the things that we're talking about. We will actually miss aspects of your personal experience. We're just bringing this to start a conversation, any conversation, get you thinking. We hope that this can be a space where we're entering with compassion for one another as each of us is a potential ally for things that we're going to talk about today.

What is Privilege?

This guy’s financial privilege is keeping him safe & secure.

We’ll start by defining a word that comes up frequently in social justice discourse: privilege.

Privilege is defined as “a special right, advantage, or immunity granted to or available only to a particular person or group.“

Privilege — whether it comes from an innate characteristic like skin color or an acquired trait like career status — puts power in the hands of a select few. It has a significant impact on those who can flex their privilege to get what they want, as well as those who suffer injustices due to a lack of these privileges.

What does privilege look like? Expand the sections below for some examples of different kinds of privilege and how they manifest in the games industry.

-

I can choose to remain completely oblivious or indifferent to the harassment that many women face in gaming spaces.

I am never told that video games or the surrounding culture is not intended for me because I am a man.

I can publicly post my username, gamertag, or contact information online without having the fear of being stalked or sexually harassed because of my gender.

If I enthusiastically express my fondness for games, no one will automatically assume that I'm faking my interest just to get attention from other gamers or game developers.

I can look at practically any gaming review site, show, blog, or magazine and see the voices of people of my own gender widely represented.

When I go to a gaming convention like PAX or GDC, I can be confident that I won't be harassed, groped, propositioned, or cat called by total strangers.

I will not be asked or expected to speak for all other gamers who share my gender.

I can be sure that my performance will not be attributed to or reflect on my gender as a whole.

-

I am able to take financial risks like starting my own studio because I have access to money.

My primary guardians / parents share generational wealth by helping foot the bill for my vehicle, college, wedding, or home ownership payments.

I think that the notion that financial gain really only boils down to working hard is accurate because that's all I had to do to experience financial freedom.

If I feel like I need to be more educated in something, I can simply purchase a class or a program like Rad Studio.

My primary guardians / parents are knowledgeable about financial literacy and help set me up for financial success in my life outside of literal money gifts.

My primary job pays me enough to live comfortably. I do not feel an urgent need to get a second job.

-

I can choose to remain completely oblivious or indifferent to the oppression that many people of color face in gaming spaces.

I can be relatively sure my thoughts about video games won't be dismissed or attacked based solely on my tone of voice even if I speak in an aggressive, obnoxious, crude, or flippant manner. (This one also applies to male privilege)

I can observe any game storefront and see images of my own race widely represented as powerful heroes, villains, and non-playable characters alike.

I probably never think about hiding my real life race online through my gamer name, my avatar choice, or by muting voice chat out of fear of being harassed for my ethnicity.

The vast majority of game studios past and present have been led and populated primarily by people of my own race, and as such, most of their products have been specifically designed to cater to my demographic.

If I'm trash-talked or verbally berated while playing online, it will not be because I'm white, nor will my race be invoked as an insult.

I can navigate tech workspaces relatively easily because they were designed by and for people like me.

I can simply exist in game spaces without feeling expected to disclose my personal perspective on issues of racism in games.

-

I can choose to remain completely oblivious or indifferent to the oppression that many disabled people face in gaming spaces.

I don't need to worry about where my job will be located or how the building is structured because most architecture is designed to fit my physical range of ability by default.

Sitting at a desk for seven hours a day consistently isn't physically unbearable for me.

I am able to consistently and reliably focus on the work at hand because I am not getting distracted by chronic pain or other symptoms.

I have access to healthcare that fits my needs.

I can easily arrange to be in the presence of people of my physical ability.

I can easily move to a new town for a new job without much hassle and I can be certain that that town will be physically accessible to me. This is huge in games because as game developers, we'll be expected to move a lot in our lifetimes because our contracts are very short.

-

I don't need to worry about "running out of spoons" before the workday has even begun.

I am able to focus clearly on the tasks at hand for the entire workday.

I interact with others with ease on teams.

I generally find it very easy to network with others.

I've never had to call out of work sick when my mental health symptoms became too overwhelming to work.

This list is not exhaustive, but hopefully these examples got your wheels turning. It’s important to note here that any of these can stack in really messed up ways. Think about how these small or large things really change how you experience the world, how welcome you feel in a space. How might they stack or add up in a game development space?

When privilege is spelled out like this, it’s clear that even things that may seem small on their own can really affect your quality of life. Having a lack of privilege in just one area is enough to impact your life, and it’s enough for those with privilege to leverage against you. As impossible as it may be to ignore for those with a lack of privilege, it’s very easy for those benefiting from privilege to skate through life for long periods of time without ever truly confronting it.

The cumulative effect of privilege (or lack thereof) leads us to our next topic: oppression.

What is Oppression?

Oppression is defined as “prolonged unjust treatment or control.”

We talk about privilege first because the word “oppression” doesn't exist in a bubble. Society and culture, privileges that we assign to certain groups, capitalism, and colonialism all feed into systems of oppression — context is important.

oppression, capitalism, and colonialism

In communities like the Ju/’hoansi tribe, sharing your fries isn’t radical or meme worthy - you’re expected to share freely with anyone who asks.

Let’s talk briefly about where oppression comes from, why it exists, and how it came to be.

We recently came across the research of an anthropologist named James Suzman. He spent 30 years working with a hunter-gatherer tribe in Southern Africa called the Ju/’hoansi. They are old-school hunter-gatherer, been doing the same thing forever. They have this really incredible system where, instead of having ownership of a thing, if you have something that somebody else needs, you’re expected to give it to them.

Here, Dana gave an example: “In our culture, if I have coffee and Megan needs coffee, Megan says, ‘Can I have your coffee?’ Then it's up to me to be like, ‘Yes, you may have it,’ or ‘No, you may not.’ I have the power. I can make Megan feel better or I can withhold it. If I have a lot of coffee, maybe I'll give Megan some, maybe I won't. Maybe I'll say, ‘You can have it if you give me $5.’ But it's mine, and I can choose what to do with it. In the Ju/’hoansi tribe, they have the opposite system. The system is of taking. If you need a thing, you just take it. Megan wants coffee or is thirsty, so Megan simply takes it. That's just how it's expected to work.”

The system that comes from that kind of culture is that you don't want to have a lot of stuff, because if you have a lot of stuff or you have more than you need, people are just going to take it. You don't have any incentive to stockpile things because it's not going to give you any power, people are just going to take it away.

Under capitalism, those with the resources have the power to withold them.

https://yellowcomics.tumblr.com/post/98850504007/not-for-puppies-support-me-on-patreon

the power to withold

Think about that for a second, and then compare that to our own system. Here, the more stuff you have, the more power you have. If you have access to resources that other people don't, it will elevate your own status within the community and will give you more power.

If I have a lot of coffee, maybe I can trade it for other stuff. Maybe I'll be more respected. Maybe I'll make sure that people put me in a position of power in all their meetings because I've got something that people want and it's up to me to decide whether or not to give it to them. Our system of capitalism encourages stockpiling. It encourages accruing status because more status means more power, means more privileges, it means more opportunities. It also encourages competition because in capitalism, the less you have, the more I have.

Oppression is linked to colonialism and capitalism. Capitalism behooves people to have more than they need because that creates power, status, privilege, and bargaining power. And then suddenly there’s competition, and this idea that the less you have, the more I have. But it has become so mainstream that we don’t often think critically about this, especially if we have a form of privilege listed before.

If you have less and I have more, that means I have power over you. It means I’m winning. It means I have more access to opportunities for security for my family to decide how the world works.

When that competition exists, oppression will necessarily exist because it's just a method to try to push other people further down, so that way you can be pushed further up. Another way to think of oppression is that it’s a way to keep power in the hands of some and take it away from others because of the idea of “you have less = I have more.” You can also look at it as gatekeeping, denying access to others.

How does this apply to the games industry?

Let’s talk about a couple of ways that oppression manifests here in the games industry.

Representation

We have a pretty real representation problem in games. Actually, such a large one that we have a whole separate workshop dedicated to it. When you're thinking about representation, you can look at three areas: who gets to be the hero, who is oftentimes the villain, and who is the target audience?

Who is the target audience

Who is this game being made for? Who does it appeal to?

Harmful stereotypes

What does the representation in the game look like? Is it authentic or based on stereotypes and tropes?

Entertainment media — games included — has a dangerous tendency to villainize queer characters, women, and BIPOC. Do the villains in the game lean on harmful stereotypes? Are they mysteriously all coded as minority characters?

Omission of entire populations over time

Who gets to be the hero? When we look at the landscape of popular games throughout history, the cast of heroes is overwhelmingly white, straight, and male.

Check out the Further Reading section below for a more detailed history of representation in games and a link to Anita Sarkeesian’s “Tropes vs Women” series. It goes super in-depth over a series of many videos about representation in video games and the tropes that come up all too often.

The Wage Gap

The games industry is no different from the international standard when it comes to the wage gap. Occupational differences between groups like men and women or white folks and black folks are driven by bias and they contribute to the oppression of out-groups. If you are seriously attempting to understand the wage gap, you should not include shifting the blame to women or BIPOC for not earning more, rather you should examine where our economy provides unequal opportunities for these folks at every point of their education, training, and career choices.

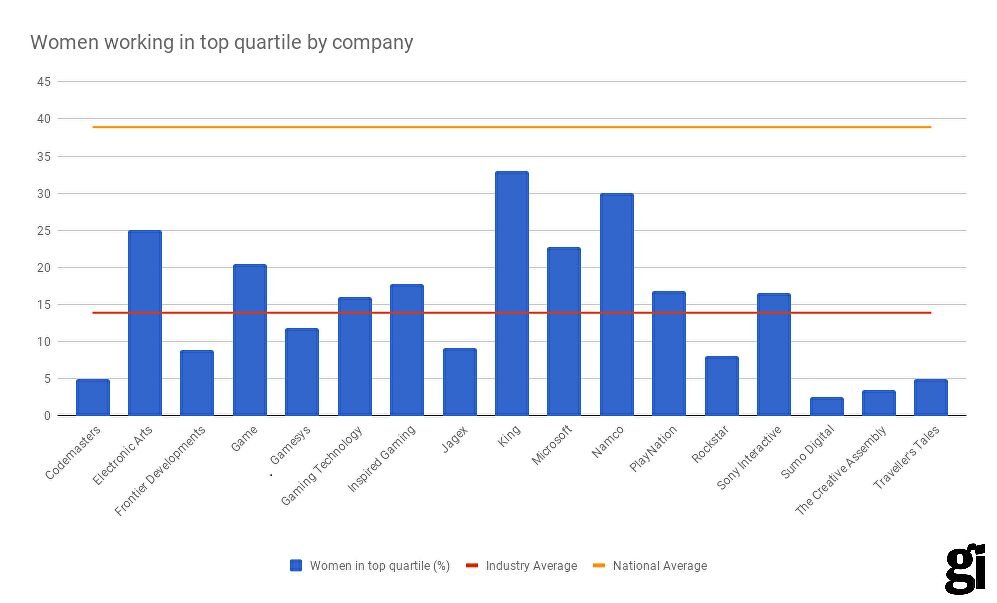

Chart from https://www.gamesindustry.biz/gender-wage-gap-deep-dive

The median national gender wage gap in Britain is 9.7%, and in the games industry, it is 15.3%. It’s a little different in the states, but the trend is the same. If you are a woman in games getting paid $50K annually, you can be pretty certain that you are making $8,000 less than your counterparts per year just for existing the way you do. That's for the same job, the same qualifications. Think of all of the things that you could do with $8,000 per year. If someone just put that in your bank account, how would that affect your life every year?

Representation in highest paid quartile - Chart from https://www.gamesindustry.biz/gender-wage-gap-deep-dive

Some other numbers we found: the average percentage of women in companies’ top 25% paid positions is 38.9%, which looks better than you might expect, but in games, it's an abysmal 13.9%. If you're talking about the lowest 25% of paid positions nationally, that amount is about 53.5% women. We noticed that nationally, there's way more women at the lowest paid positions than there are at the highest paid positions. In games, the highest amount of representation is at this lowest paid quartile, which aligns with that national downward trend is 27.3%. There just are not as many women in games; our workforce is tilted in a pretty male direction.

Under capitalism, if you want to keep a group oppressed, just don't pay them. Don't let them get to the top.

Representation at the lowest-paid quartile — Chart from https://www.gamesindustry.biz/gender-wage-gap-deep-dive

(The source for this data is GamesIndustry.biz — see further reading section for more.)

It's not just the industry that causes this, it's also your educational space. Oppression in the educational space also ties into crunch culture, unfortunately. Crunch in and of itself is oppressive and it is also a system of oppression. It has extremely negative physical and mental health effects on all people who participate. We know it doesn't even get that much more work done, and yet game companies are still using it as a main structure in their workflow.

#1reasonwhy and #MeToo

In 2012, the #1reasonwhy hashtag started circulating around “gamedev twitter.” It came up because a developer, Luke Crane, tweeted the question: “why are there so few lady game creators?” Game developers started responding with the hashtag #1reasonwhy. It snowballed with tons of people sharing their experiences and why they don't make games anymore.

“Because I get mistaken for the receptionist or day-hire marketing at trade shows. #1reasonwhy”

“Because I'm sexually harassed as a games journalist, and getting it as a games designer compounds the misery. #1reasonwhy”

“My looks are often commented on long before the work I've done. #1reasonwhy”

These are a few examples of tweets that came out. They talked about having their work dismissed and ignored, having designs for non-sexualized female characters rejected, having their clothing and appearance being used to dismiss them on gender grounds, and then on more extreme end, sexual harassment and worse. I'd say this was evidence of the gatekeeping and the oppression building up enough that marginalized people were straight up leaving the industry.

We all know about the Me Too Movement in the greater world. There's been quite a few waves of the #MeToo hashtag and in 2020 during the pandemic, games Twitter exploded with our industry’s ”Me Too” stories. There were dozens if not hundreds. Our Twitter feeds were full of testimonies that began to surface.

It was truly a heartbreaking dumpster fire. There were tons of testimonies describing incidents of rape, assault, harassment, threats, extortion, abuse of authority, exploitation of underage girls, and several counts unique to the digital industries, such as online bullying and leaked intimate photos. As one example: In August 2020, Ubisoft reportedly fired their editorial vice president Tommy Francois, who allegedly pursued sexual relationships with female subordinates or touched female employees without consent during work and sent employees sexually harassing messages. He was fired. Then two weeks later at the same studio, the Assassin's Creed Valhalla creative director Ashraf Ismail was fired after being accused of systematically trying to engage in sexual affairs with young women in the industry by leveraging his role at the company and lying about his marital status.

GDC: Inaccessibility and party culture

GDC, the Game Developers Conference, is an indispensable resource in our industry. Unfortunately, it also serves as a barrier to some of the most vulnerable members of the community. There’s an attitude that everybody who’s anybody will be at GDC each year, but the event is inaccessible to many of us. You have to travel a long distance to get there. You have to spend a lot of money to buy a ticket. The actual venue is technically physically accessible, but the fact that it’s based in San Francisco is less physically accessible — it's all hills. The party culture that’s pervasive in many game studios is amplified at the afterparties and networking events. There is a very serious culture of alcohol and partying at GDC that doesn’t get brought up to students enough because it affects you the most.

A lot of people use partying to network, and students are vulnerable to this party culture, especially when it comes to sexual assault. It seems innocuous at first. You might be at a party and someone will offer to buy you a drink to talk to you and you're like, "Wow, a lead character artist wants to talk to me! Oh my God, am I going to get hired?” Then all of a sudden, they start commenting about how cute you are and how you'll be fine in this industry because you’re so cute, and ask you to another party.

We want you to know as students that that is an abuse of power. When somebody does that to you, walk away, because you are there to network and they are there to take advantage of their position over you for flirting or more, usually more. It's gross and it is terrifying — it is actually terrifying, because you also feel like you can't reject them, or you’ll fumble your only chance at a job in your field. Predatory behavior like that drives home a feeling of not belonging or feeling like you will only be invited in for your looks or your perceived gender. It's oppressive.

One of the “lucky” ones

Privilege = Access

Privilege is access, and if you have it, you use it. Every day you're using it or other people use it on you. You have access to education, you have access to tools and resources, access to jobs, access to promotions, access to higher pay, credit, representation, money to invest in your own indie studio or your own game or side project, and childcare so that you can work long hours while having a family.

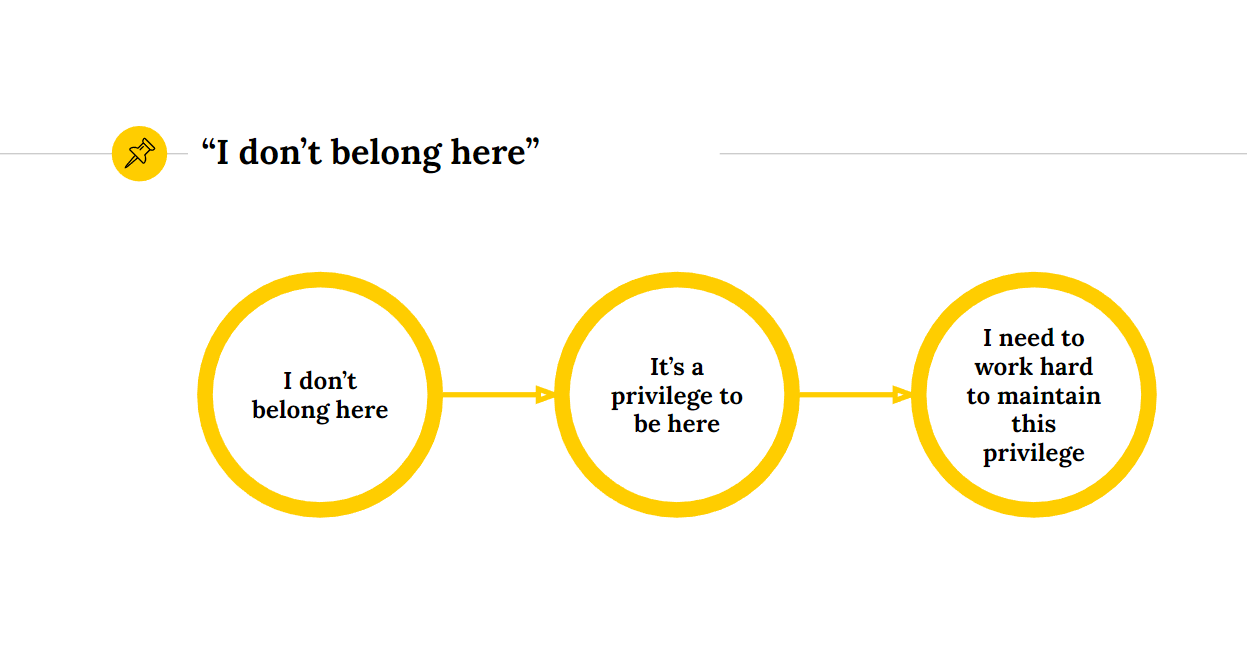

When you have really strong gatekeeping to a community or a workforce, when you have that giant leap of an obstacle to get over just to get in, you're entering with this notion of “I don't belong here.” Of course, we have terrible imposter syndrome because it was hard enough to even get in. Then we start to think, "It's a privilege to be here. I'm one of the lucky ones. I got a job in games. How lucky am I?" Then we start to think, "I need to work really hard. I need to overexert myself to maintain this privilege."

This is a system of oppression is because the person that this benefits is not you, it's someone up the food chain from you. You shouldn't have to feel that need to over-exert just to prove your worth. They hired you because you're worthy. This should be implied by your presence. All too often, an unhealthy workplace will take the opportunity to exploit you further if you show that you’ll put up with mistreatment or overwork out of a sense of not belonging.

How to Be an Ally

Why is it important to educate yourself on this stuff? Allyship — protecting others — or protecting yourself. Understanding where and how oppression exists will help you understand how to make games, in general, a more equitable space.

Allyship is active

Megan came across a zine once that said:

"Everyone calls themselves an ally until it's time to do some real ally shit."

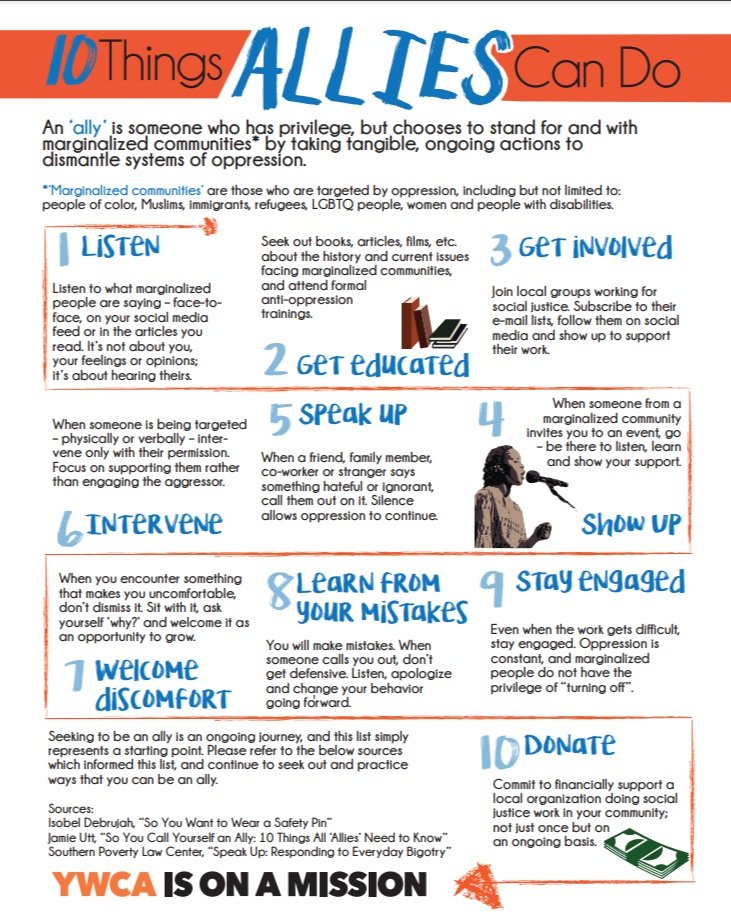

The main lesson here is that allyship is a verb. You have to always remember this. The absolute bare minimum entry point to allyship is your set of beliefs. Real allyship only happens when the actions that you take align with allyship, meaning that your beliefs are reflected in your actions in a way that supports other people in a quantifiable way. Some examples of this are donating, challenging the status quo in a way that makes a more equitable workspace, voting, talking to your friends and challenging their fucked up beliefs, sharing knowledge, literally protecting your friends, having friends you can protect. To stand there unmoving in your corner of the internet saying, "I believe that this is oppression of another and that's wrong," but not actually physically doing anything about it is not in fact being an ally. It is the tip of the iceberg, it is performative allyship to do that.

To speak to allyship and not to act is performative. You understand that there's a problem and you choose to talk about it instead of standing up and doing something about it. This shouldn’t be conflated with talking about things and educating others as an example of allyship. That's a little different than posting to your Instagram story and being like, "Man, I wish that this bill wasn't being passed. Did I vote about it? No, I didn't. Oh, but I wanted to, I just didn't." Performative allyship is when you profess support and solidarity with a marginalized group in a way that isn't helpful. It's also known as performative wokeness. Allyship is a consistent lifelong practice of unlearning and re-learning in which a person in a position of privilege or power seeks to operate in solidarity, not just speak in solidarity. Not centering yourself, but supporting others.

How can I practice allyship?

Check out the list in the infographic to the right from YWCA.

Step one is research. Look into the links we provide below. Think critically about them, but also listen to the people who are affected by the thing that you're trying to learn about.

Don't practice performative allyship, really try to remember that allyship is a verb, repeat that mantra to yourself. Try to ground your allyship in action, and get comfortable being uncomfortable.

In many ways that means being comfortable with being uncomfortable speaking up within your social circle. As an example, from a white perspective, I grew up in a mostly white town, my social circle was white. To begin anti-racist work, I had to be very comfortable getting uncomfortable and making other people uncomfortable.

It also means finding a way to get into that discomfort of saying, "This action is not okay." You might make it more palatable by saying “I'm not attacking you, I'm attacking this action, because this action/phrase is unacceptable.”

You can also amplify the voices and messages of marginalized people and simply show up. That can mean going to activist events, or when your friend is like, "Hey, I have to go through this really hard thing," choosing the on-ramp, and listening and showing up for that friend.

Showing up

In Megan’s words: “One way that Dana showed up for me without me asking or expecting it, is that we were recently like in a group of people at a picnic and we didn't know all of them, and Dana showed up to the picnic a bit later than everyone else. When Dana arrived, she was like, ’Hey, I'm Dana, my pronouns are she/her, what are yours?’ to everyone in the group. Everyone said their pronouns very nonchalantly. Then people knew that I was gender-neutral and that my pronouns are they/them without me having to read that conversation or be vulnerable in order to start that conversation.”

We also wanted to share a little bit of a harder story because sometimes, to be an ally and "do some real true allyship" can cost you. Systems that are in place do not like to be challenged. That's the first step of what your discomfort is telling you. It's like, "I'm about to challenge a system and systems don't like to be challenged."

story time

“I was asked to recommend two people who I thought would be a good fit to work with me in my department. I had recently graduated with a Game Art degree and I recommended two people who I had graduated with — two of my friends who were actively struggling to secure jobs in the industry. One was Latinx and one was Black. I thought to help them get a job where I worked would be a form of allyship, and I wanted to help free my friends from their current job-search struggles.

“When these friends got hired, I found that I was being paid 25% more than them. I had only been there three months longer. We had the same degree, same qualifications, same graduating class. We had similarly developed portfolios and were all on a pretty equal art playing field. I knew working with these people would be good because we were all on par. I thought we were equals, so I was shocked to learn that I was making significantly more than them.

“That sounds very illegal, but it's actually not illegal and it happens a lot. A lot of companies will try to put into place a ‘do not ask your coworkers what their salaries are’ policy and very specifically try to keep you in the dark. This company had one of those — which infringed on our right to disclose and discuss our wages. Companies in Vermont cannot bar you from asking other employees what they're making, but they can pay you whatever they want and whatever they can get away with - so that’s what they did.

“At the entry-level this was infuriating. It made me really upset. I called a meeting with my supervisor immediately. I told him that his choice to pay each of the new employees significantly less than me per year was unethical and wrong, which he acknowledged. I walked him through why and how, and I called attention to the fact that we all had the same exact education and similar work history. He seemed to take this really well. He was like, ‘This is a big deal!’ In that meeting he said he'd fix it right away. I was shocked because this place was not a healthy workplace, and I was feeling proud of myself for standing up for my peers.

“He gave each of them raise — a raise that only accounted for half of the difference between our salaries. It shortened our wage gap but did not create equality, and he also called a meeting with me to say, ‘Since you’ve been here for three more months than them, maybe you should have a leadership role over them.’ He did not offer me a pay increase for this leadership role. He was assigning me more of a responsibility for no additional pay to justify his unequal treatment of me and my coworkers. This did not remedy the situation for me.”

This story unfortunately does not have a happy ending — it ended in overwork, further mistreatment on the job, and ultimately with this person being fired from the company. The first moral of the story is that there is stuff to lose from being an ally. It's not always peaches and cream. The other lesson to learn here is to get a solid feel and vet the workplace before recommending friends who might face discrimination there.

It’s not always a choice.

In this story, there’s another element at play: the privilege to negotiate. The speaker’s higher salary was negotiated up from the original offer. They made the choice to negotiate, but not everyone has that luxury. It's not always your choice. Both of the new hires were not financially privileged, they were actually quite desperate to get a job. That lack of financial privilege intersected with lack of racial privilege.

“I made the unfortunate choice to ask my friend the question: ‘Why didn't you negotiate harder?’

“They were like ‘Because I can't man. What the fuck.’ I was like, ‘Oh you are so right.’

“That was a failure that I learned from, but this is the same: Why didn't they just choose not to work there? It’s a similar ignorance that we can learn from. It's not always a choice.”

in contrast

The example above didn’t have a happy ending, but it doesn’t have to be that way. We shared another example in contrast:

“It’s true that the systems don't want to change, but a lot depends on who you're talking with, who the people are in the company who the company is, what their values are, and how big the company is. If it's a really big company, you’re going to have a harder time steering that ship than maybe a smaller one.

“I wanted to share a short story about my friend who works at the restaurant. He's a white man. He was doing some delivery during the pandemic. He was wearing a Black Lives Matter mask every day while he was bringing food out to people's cars and stuff. Then one day the manager was like, ‘Starting tomorrow, no one is allowed to have to wear any masks that have any writing on them.’ He looked around and pretty much everybody had blank masks except for him. He felt it was a real clear dig at not wanting to advertise affiliation with Black Lives Matter.

“He had a choice to make and he went to them and he chose to do the harder thing. For him, it wasn't the harder thing but I think he put himself in a vulnerable position where he said basically like, ‘I'm going to wear this mask and you can fire me if I can't. That's the thing. It matters a lot to me.’ He told them why it matters. He had a conversation with the management.

“They came back a few days later and said, ’You know what? You're right. Keep wearing the mask.’ And he actually had a better relationship with his manager moving forward. I just wanted to share that short story to illustrate that it really depends on the atmosphere of the people, the company, and what you're asking. Sometimes it will be great but sometimes it won't be, sometimes you'll get pushed back and it will be hard.”

Allyship is looking out for others

As we mentioned above, be careful recommending people for jobs that might be unsafe. It should be our own personal responsibility to vet companies before we get there to make sure it's going to be a healthy, good fit, but whenever we're in a potential position of having more insight, then we should also take some responsibility to be looking out for our friends.

Sometimes companies reach out to Rad Magpie to ask, "Hey, will you send us some of your students?" We'd love to send students over for job opportunities, but we will never send any of you to a company that doesn’t meet our standards. We just won't do that. That's part of our job as allies looking to look out for others.

The baseline way we do that is asking questions like “How much are you offering to pay new hires?” "What's your diversity, equity, and inclusion policy?”

As an organization, we have a safe-space policy. We have an equity policy. We create equal pay. We can enforce all of these policies. We wanted to talk about what you can do in leadership because some of you want to start your own studio or organization, and we want you to do that, but we want you to do that intentionally. Think about what we've talked about here today.

When you're walking into workspaces and seeing other people being mistreated, we don't want you to say, "That's their problem. They chose this." Or, "That's their problem, it doesn't affect me." Or “It's not that bad.” Never minimize someone else’s lived experience.

Microaggressions add up

Take another look at our Safe Space Policy. In this policy, we define harassment and assert that we have no tolerance for harassment in our spaces.

Think about how harassment leads to gatekeeping, leads to oppression. Unwelcome sexual attention isn't just bad because maybe it makes me feel icky and uncomfortable. It's also bad because these tactics have been used for a very long time to make people of certain groups feel unwelcome in a space. It is disempowering. It is oppressing.

Some of these actions might make you think, in a vacuum, "It's not that bad." You just asked for their number when they were having a work discussion. It's not that bad. That single action may feel harmless, but consider how people experience discomforts like that on a regular basis. Those discomforts add up enough to make it incredibly difficult to feel safe and welcome in a space.

That's why we don't do it. It's not just the small thing. It is contributing to a system of oppression that's keeping people out, keeping people from being welcome in that space, and affecting them on a lifelong level in a negative way.

You can prevent some of that harm by taking responsibility for yourself and your actions and knowing when something is harmful and choosing not to do it.

What can you do?

Many conversations about allyship center on harmful behaviors to avoid, focusing on what you shouldn’t do. But what can you do, proactively, to be an ally?

Work towards creating a community where others feel welcome, like they belong there. We talked about this before, but that's so much of what allyship is: how can I look around and make people feel like they belong? Feel like we're happy that they're there, that they're safe?

That is the positive call to action. Avoid all that bad shit, avoid the oppressive things. Your positive call to action is everyone doing their part to make that space welcoming and equitable.

Your other call to action is to keep it up. Don't do it for five months and then be like, "I'm done, I'm tired." We'll go back to oppressing.

This is a lifelong commitment.

As we wrapped up the presentation, Dana offered one final comment about the creation of the workshop:

“Full disclosure, Megan and I spent a lot of time earlier this year trying to come up with workshop activities around this topic, discussion opportunities, and everything. We couldn't find something that we felt 100% comfortable would not be placing undue burden on marginalized people.

“We don't want to make anybody talk about stuff that they are not comfortable talking about, because everybody in this room comes from a different background. Hence why we have an unceremonious end to our presentation. I feel our call to action is first off do your research. Know what you're getting into, and know how to protect yourself and how you can do your part to protect other people.”

And with that unceremonious end, we’ll leave you to explore the slide deck and additional resources below:

Presentation Slides

A video recording of the presentation will be shared here when we have completed our editing process. Don’t worry, you’re not missing any content in the meantime: all of the information has been transcribed into this blog post. However, we intend to share recordings of each presentation for those who would prefer to listen along. Check back soon if you’d like to watch the video.

Rules of Use

This blog post is based off of a portion of the 2021 Rad Studio Online curriculum. Rad Studio 2021 was a fully online summer program for game development students, and the information above was shared with the cohort of emerging devs during a workshop session. We’re making this information free and available to anyone who’s interested in it. You can learn more about Rad Studio and this initiative here.

Rules of Use:

Feel free to share this information with others! We ask that you cite Rad Magpie (and any relevant linked sources) if you use this for your class / workshop / etc.

If you find this useful and are financially able, consider making a donation to Rad Magpie. We’re a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization and rely on the generosity of our community to continue producing resources like this one. Learn more about Rad Magpie here.

Further Reading

“Tropes vs. Women in Video Games” video series by Feminist Frequency - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X6p5AZp7r_Q&list=PLn4ob_5_ttEaA_vc8F3fjzE62esf9yP61

“End game: How #MeToo is disrupting the gaming industry” article by Amit King - https://www.calcalistech.com/ctech/articles/0,7340,L-3847870,00.html

“#1reasonwhy: the hashtag that exposed games industry sexism” article by Mary Hamilton - https://www.theguardian.com/technology/gamesblog/2012/nov/28/games-industry-sexism-on-twitter

“Exploring the pay gap: What does the data really say about the industry's gender imbalance?” article by Ivy Taylor - https://www.gamesindustry.biz/gender-wage-gap-deep-dive

“Affluence Without Abundance: The Disappearing World of the Bushmen” book by James Suzman

“Representation in Games” article by Dave Eng - https://www.ludogogy.co.uk/article/representation-in-games/

“10 Things You Can Do to Be an Ally” infographic by The YWCA of Greater Harrisburg - http://www.ywcahbg.org/sites/default/files/manager/10%20Things%20Allies%20Can%20Do.pdf

This blog was written by Maggie DeCapua based on a presentation prepared by Megan McAvoy and Dana Steinhoff.